Black women are finding unique ways to plan for retirement, included changing careers and their mindsets.

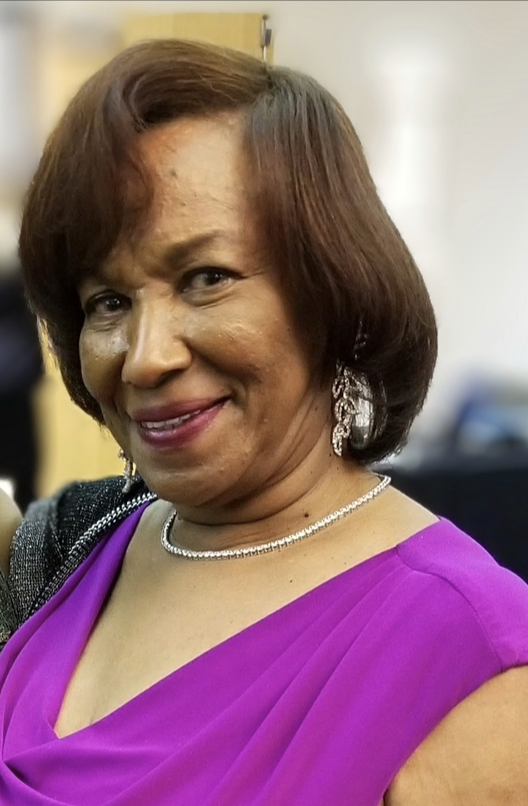

Freddie Davis-English, a retired government administrator from Minneapolis, was sought after for her previous accomplishments and propelled into a new career in the non-profit sector. While her retirement investments, pension and Social Security were able to afford the retirement she’d envisioned for herself, she was open to professional growth and the opportunity to help others.

Davis-English was more financially prepared for her retirement than she thought. A forgotten supplemental retirement policy in the high 5-figures gave her financial assets a boost.

“It was a welcomed surprise when I retired because there was a time when they wanted to get rid of it as a cost-saving measure. An older co-worker talked me into keeping it instead of cashing it in.”

She was able to use the money from the supplemental insurance policy to pay for her daughter’s wedding and many other milestone occasions without tapping into her pension and additional retirement savings. Even without working post-retirement, she was able to thrive off the retirement assets she’d accumulated. When you add her husband’s retirement assets to the mix, their lifestyle is equal to their pre-retirement income.

However, Davis-English is the exception, not the rule.

Dr. Angelino Viceisza, Professor of Economics at Spelman College in Atlanta, and research associate of the National Bureau of Economic Research, says that Black women have many structural barriers to achieving financial stability in retirement.

In his brief, “Black Women’s Retirement Preparedness and Wealth”, Viceisza studies single Black women and notes that they have an average retirement wealth of $11,157, the second-lowest average retirement wealth after Hispanic women. This means, as a group, they are not considered retirement-ready, and in fact, they often retire into poverty.

According to the Social Security Administration, in 2021, $13,363 ($1,113 per month) was the annual average Social Security income received by Black women 65 years and older. The maximum Social Security benefit available in 2023 is $4,555 per month, depending on lifetime earnings and age of retirement. The earliest age to begin collecting Social Security retirement benefits is 62. With Black women’s life expectancy at 75 years, there isn’t much time or resources to enjoy the golden years.

Viceisza finds that employment discrimination, low housing equity, health drains on savings and limited intergenerational wealth transfers are key factors contributing to low levels of retirement wealth for Black women. While they have a slight edge over other women in financial literacy, that isn’t enough to change their circumstances.

“There is a financial literacy component to why perhaps they’re not as prepared for retirement. The real big component is that they just don’t have enough wealth that they are inheriting, generating and are able to pass along to their children.”

He believes that Black women reinventing themselves after retirement is a way to circumvent the economic disparity.

At age 49, Darling “Diva” Moore of Denver, Colorado, did the math on her retirement.

“I started saying, ‘Wow, I am about to turn 50, and the only thing I have to look forward to is Social Security’. And when I looked at it, I saw shoe money.”

Moore’s plan is to retire at age 62, and she will receive $2,000 monthly from Social Security. If she had chosen to wait until age 67, her Social Security income would only increase by $100 per month.

When she looked at the numbers, that was not enough to afford the lifestyle she was currently living with her husband if he were to pass away first.

“When you tell a man, your man, your husband, ‘I’m worried about what would happen to me if something happened to you,’ the first thing out of their mouth is to remind you they have life insurance.”

Statistically, Black men live on average to age 69, leaving many wives to live out their retirement as widows. Moore and her husband crunched the numbers together to gain a mutual understanding.

“I literally had to sit down with my very educated husband, who’s an engineer and got math on lock, and show him that, ‘the money put away for me to live off if you’re gone, don’t even take care of our mortgage, Boo’.”

With this revelation and her husband’s support, she spent a year devising a plan to reinvent herself to supplement her income.

At age 50, she finished her bachelor’s degree and immediately started on her master’s. Her plan is to work in corporate until retirement and then use her newly acquired education to pivot into entrepreneurship as a private practice social worker.

In the meantime, she provides counsel to other women to get their Social Security Statements early to prepare for retirement. Her main focus is to help them figure out what they “want to be when they grow up” and devise a plan to make it a revenue stream.

Viceisza found that some who aren’t able to pivot into working after retirement often look to their children as a source of help to supplement their lifestyle.

Moore says that’s not an option.

“I have no intention of living with my daughter; I see the way she keeps her house.”

Dorothy Bridges of Minneapolis has over 45 years of working in the financial services industry, and she teaches her children and others about financial security. She has yet to retire, and although she feels prepared, that wasn’t the case early in her career.

“I learned a few things going through the school of hard knocks because I don’t think we even think about asset building when we are fresh out.”

Bridges says Black women should begin thinking about retirement as an investment in themselves. She advises starting as early as possible and looking into hiring a professional to help navigate the process and find the right mix of assets, such as real estate, stocks, savings accounts and 401(k)s.

“Make sure you understand that when you’re very early in your career, you may not be able to afford to put away the maximum into your 401(k) or other assets, but at least try to put away enough for the company to match your contribution.”

Bridges comes from a family of sharecroppers in Mississippi and knows the obstacles of learning about finance on your own, growing up without an inheritance, and the difficulty of saving when you may want to spend. She understands the need to sacrifice, change course and start fresh.

“I tell my kids, ‘short-term sacrifice for long-term gains’.”