Posts Tagged ‘#Blackwomenmentalhealth’

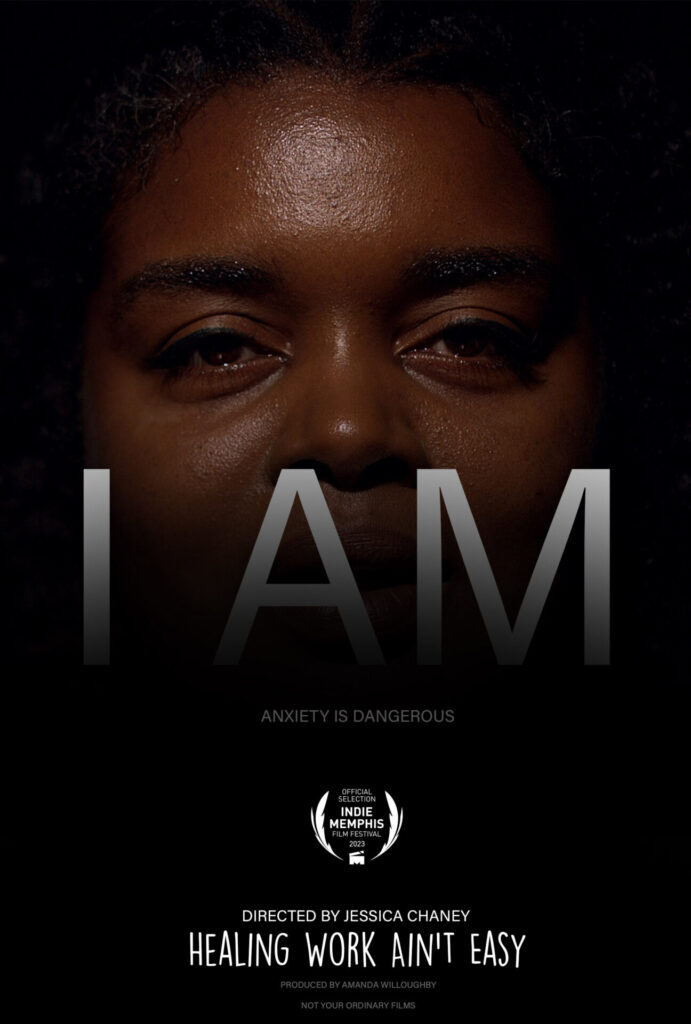

I AM: Telling Black Women’s Stories of Coping and Thriving with Anxiety

Founders of Not Your Ordinary Films (NYOF), Jessica Chaney and Amanda Willoughby are the creators behind “I AM”, a documentary that launched in October. “I AM” centers on Black women who live with anxiety, tells stories about coping and thriving with a disorder that is often overlooked and misdiagnosed in Black women. Films that center Black women are often void of Black women working behind the camera and on the scene to ensure the voices are protected and the stories are told with honesty and dignity. These two women are changing the industry by choosing a career in film that centers Black voices through a mirroring lens.

Chaney and Willoughby met as co-workers at a Memphis Public Library and found a kinship in their shared desire to make movies. Willoughby, a graduate of the Memphis College of Art and a filmmaker, is the producer and editor for the project. She says their goal is to normalize Black people in mass media and tell the stories that are typically on the margins.

“We don’t want to make stereotypical Black content. We just want to tell everyday stories, normal stories, and these characters happen to be Black. Whatever comes along with being Black is going to show up in this story somewhere, anyway, because it’s our reality.”

“I AM” shares the dangers that lurk behind the shadows of anxiety that can render Black women strangers to their own thoughts. The force of this mental health disorder unveils the stark reality of the pressures and unfulfilled desires that silence Black women and often leave them to face the world alone.

The film was born out of personal experience for Chaney, director of the project, who suffered for years with anxiety. After participating in a director’s program at the University of South California (USC), she realized that telling her own stories could be a way to help others.

“Even from the time I was little, I’ve just genuinely enjoyed listening to people. I think people don’t understand how much others just want to be heard.”

Being understood and validated was a personal struggle for Chaney who for a very long time felt invisible. Although she has come to terms with this reality as a Black woman, some incidents still trigger these feelings.

“The other day, I was in Fresh Market, and I was in the middle of the aisle. Now, I am a fuller-figured girl, and I am in the middle of the damn aisle, and this white man was like, ‘Oh, I didn’t even see you there!’ And I was like, ‘Sir, how did you not see ME and be bold enough to tell me?’”

The women in the film are boldly telling their truths, unfiltered and uncensored. Like Chaney, they experienced exhaustion, frustration, depression, hurt and anger and realized they wanted more from life than these feelings that were holding them back.

Willoughby believes many aspects of Black women’s lives contribute to their anxiety, including racism, societal pressures and being expected to carry the burdens in all aspects of their lives. She says many Black women “Have the feeling that ‘if I do break, nobody is there to catch me, so I can’t be the one to break’.”

Chaney says that unlike other women, Black women are not allowed to have a full range of emotions. She wants this film to give Black women permission to feel joy.

Willoughby’s goal is for the film to resonate with Black women who want others to see their humanity.

“It comes back to people calling us intimidating, or I’ve heard aggressive, yet we’re always expected to be on top of things, and sometimes I am just winging it.”

They both acknowledge that Black women are often thrust into jobs and careers that can provide security for their families, sometimes forgoing their aspirations.

Chaney explains that becoming filmmakers has been a healing journey for them.

“Black women, we’re the doers and a lot of times, we don’t get the liberties to be the dreamers and the thinkers.”

She believes there is a huge pool of untapped talent among Black women who can be deterred by a lack of resources and guidance, which can lead to anxiety that shows up as irritability, anger and frustration.

“As they grow as women and in their careers, they are unlearning behaviors embedded for generations, such as justifying wanting beautiful things, taking trips or changing careers.”

She believes that telling important stories from their perspective is a calling.

“It’s so important for us to be in this position where we are able to take ownership of these stories. This is where we feel most comfortable and where it feels like joy.”

Workplace Trauma: masking + anxiety + depression + PTSD

Masking is a mental health term that describes ways to hide, suppress or camouflage symptoms of anxiety, depression and post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD). In the workplace, it refers to fitting into the cultural environment to maintain your job and relationships without anyone knowing what is going on inside. For Black women, masking happens often, and long term, it can spike the stress hormone cortisol leading to mental and physical health issues.

“We’re so into mask-wearing that we don’t pay attention to what our internal sensor, our intuition, our common sense is telling us,” says Dr. Angela Neal-Barnett, director of the Program for Research on Anxiety Disorders in African Americans (PRADAA) at Kent State University in Ohio.

Neal-Barnett says dreading going into the workplace could indicate one is struggling with anxiety or depression. “If you’re out in the parking lot willing yourself to go into the building, okay, that’s a sign that something is wrong not only in the workplace, but you want to take stock of your anxiety, depression and PTSD.”

“Anxiety can show up as agitation, irritability, hostility and anger, which can feed into the ‘angry Black woman’ stereotypes we often try to avoid.”

Symptoms of anxiety disorders can present differently in Black women. “Anxiety can show up as agitation, irritability, hostility and anger, which can feed into the ‘angry Black woman’ stereotypes we often try to avoid,” says Dr. Shaakira Haywood Stewart, a psychologist in New York.

Seeing anger in Black women can illicit negative labels from others. “We’re quick to say, ‘she’s crazy,’ but not necessarily recognizing the number of boundaries that person has had crossed, and the resentment that can build up from years of neglect or emotional trauma,” says Dr. Afiya Mbilishaka, head of psychology at the University of the District of Columbia, hairstylist and founder of PsychoHairapy.

While many avoid being angry because of the stereotypes and labels, embracing that emotion can be a healthy choice. “Getting angry is better than internalizing it,” says Neal-Barnett. “Because what happens when you internalize it? It’s all your fault. But racism, which is what you’re experiencing, is not your fault.”

Another symptom is being in a perpetual state of fatigue. “Exhaustion can be a silent killer,” warns Haywood Stewart. “You’ll hear from patients, ‘I’m so tired,’ and they think it’s because of working a lot, but it can lead to hypertension, pre-diabetes and fibroids.” Haywood Stewart cautions against preoccupation with trauma, which can manifest through repetitive discussions about the traumatic events, persistent flashbacks and recurring dreams of the incidents. It is important to find an outlet and someone to talk to about the issues that are causing mental anguish.

“Getting angry is better than internalizing it.”

For many Black women, the initial person who notices something is wrong may be an unlikely source. “Probably the first person who’s going to tell you something is wrong is your hairdresser,” says Neal-Barnett. They often hear about the issues in-depth, and see you regularly enough to be aware of mental and physical changes. For this very reason, she has a licensed hair professional on her research team because she says they are vital in diagnosing mental health issues. “You may sit in the chair and hear, ‘Girl, what is going on?’ because our hair tells a story about what we are going through.”

At that point, Neal-Barnett emphasizes the importance of seeking mental health assistance, making an appointment with your physical doctor and seeking legal advice—which may be difficult for some as they worry about the stigma associated with complaining and their job security. “For many women, they feel if they are not working, then what happens to the family in terms of keeping a roof over people’s heads.” She recommends using accrued Personal Time Off (PTO) for self-care and talking to your doctor about whether using resources, such as the Family Medical Leave Act (FMLA), are options.

When asked if the workplace is safe for Black women, Haywood Stewart answered emphatically, “No, it’s not.”

The workplace can be a harmful environment, and it is easy for Black women to become complacent and accept marginalization when it has become commonplace. “Some of the things happening to us in the workplace are traumatic and harmful,” says Haywood Stewart. “We’ve become used to being harmed because it happens over and over again.”

When your symptoms begin affecting personal relationships outside of work, that’s a sign that you need to seek help. “When the people you love start avoiding your calls, you find friendships and romantic relationships deteriorating; it’s time to get help,” says Haywood Stewart.

Neal-Barnett highlights that although workplace-induced stress can feel isolating, talking to others about these experiences is important. “You are not alone, and you are not the only one.” She says that it happens every day in corporate America and academia, which has adopted a corporate model. She explains that Black women may need to venture outside of their comfort zones if they want to see changes in their lives. “I know it feels embarrassing, and you feel shame, but if you can set aside that feeling for one minute and tell someone else who is Black, you are going to find hope and a plan to move forward.”

head of psychology at the University of the District of Columbia, hairstylist and founder of PsychoHairapy

psychologist

director of the Program for Research on Anxiety Disorders in African Americans (PRADAA) at Kent State University in Ohio