Careers

I AM: Telling Black Women’s Stories of Coping and Thriving with Anxiety

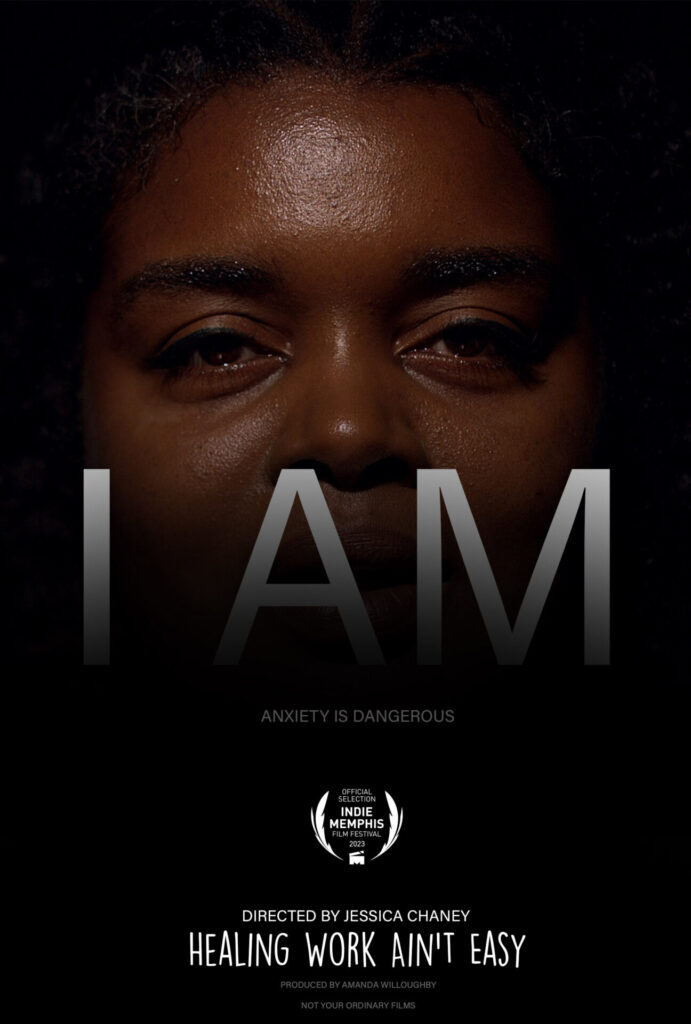

Founders of Not Your Ordinary Films (NYOF), Jessica Chaney and Amanda Willoughby are the creators behind “I AM”, a documentary that launched in October. “I AM” centers on Black women who live with anxiety, tells stories about coping and thriving with a disorder that is often overlooked and misdiagnosed in Black women. Films that center Black women are often void of Black women working behind the camera and on the scene to ensure the voices are protected and the stories are told with honesty and dignity. These two women are changing the industry by choosing a career in film that centers Black voices through a mirroring lens.

Chaney and Willoughby met as co-workers at a Memphis Public Library and found a kinship in their shared desire to make movies. Willoughby, a graduate of the Memphis College of Art and a filmmaker, is the producer and editor for the project. She says their goal is to normalize Black people in mass media and tell the stories that are typically on the margins.

“We don’t want to make stereotypical Black content. We just want to tell everyday stories, normal stories, and these characters happen to be Black. Whatever comes along with being Black is going to show up in this story somewhere, anyway, because it’s our reality.”

“I AM” shares the dangers that lurk behind the shadows of anxiety that can render Black women strangers to their own thoughts. The force of this mental health disorder unveils the stark reality of the pressures and unfulfilled desires that silence Black women and often leave them to face the world alone.

The film was born out of personal experience for Chaney, director of the project, who suffered for years with anxiety. After participating in a director’s program at the University of South California (USC), she realized that telling her own stories could be a way to help others.

“Even from the time I was little, I’ve just genuinely enjoyed listening to people. I think people don’t understand how much others just want to be heard.”

Being understood and validated was a personal struggle for Chaney who for a very long time felt invisible. Although she has come to terms with this reality as a Black woman, some incidents still trigger these feelings.

“The other day, I was in Fresh Market, and I was in the middle of the aisle. Now, I am a fuller-figured girl, and I am in the middle of the damn aisle, and this white man was like, ‘Oh, I didn’t even see you there!’ And I was like, ‘Sir, how did you not see ME and be bold enough to tell me?’”

The women in the film are boldly telling their truths, unfiltered and uncensored. Like Chaney, they experienced exhaustion, frustration, depression, hurt and anger and realized they wanted more from life than these feelings that were holding them back.

Willoughby believes many aspects of Black women’s lives contribute to their anxiety, including racism, societal pressures and being expected to carry the burdens in all aspects of their lives. She says many Black women “Have the feeling that ‘if I do break, nobody is there to catch me, so I can’t be the one to break’.”

Chaney says that unlike other women, Black women are not allowed to have a full range of emotions. She wants this film to give Black women permission to feel joy.

Willoughby’s goal is for the film to resonate with Black women who want others to see their humanity.

“It comes back to people calling us intimidating, or I’ve heard aggressive, yet we’re always expected to be on top of things, and sometimes I am just winging it.”

They both acknowledge that Black women are often thrust into jobs and careers that can provide security for their families, sometimes forgoing their aspirations.

Chaney explains that becoming filmmakers has been a healing journey for them.

“Black women, we’re the doers and a lot of times, we don’t get the liberties to be the dreamers and the thinkers.”

She believes there is a huge pool of untapped talent among Black women who can be deterred by a lack of resources and guidance, which can lead to anxiety that shows up as irritability, anger and frustration.

“As they grow as women and in their careers, they are unlearning behaviors embedded for generations, such as justifying wanting beautiful things, taking trips or changing careers.”

She believes that telling important stories from their perspective is a calling.

“It’s so important for us to be in this position where we are able to take ownership of these stories. This is where we feel most comfortable and where it feels like joy.”

Retirement: Reinventing Yourself for Financial Freedom

Black women are finding unique ways to plan for retirement, included changing careers and their mindsets.

Freddie Davis-English, a retired government administrator from Minneapolis, was sought after for her previous accomplishments and propelled into a new career in the non-profit sector. While her retirement investments, pension and Social Security were able to afford the retirement she’d envisioned for herself, she was open to professional growth and the opportunity to help others.

Davis-English was more financially prepared for her retirement than she thought. A forgotten supplemental retirement policy in the high 5-figures gave her financial assets a boost.

“It was a welcomed surprise when I retired because there was a time when they wanted to get rid of it as a cost-saving measure. An older co-worker talked me into keeping it instead of cashing it in.”

She was able to use the money from the supplemental insurance policy to pay for her daughter’s wedding and many other milestone occasions without tapping into her pension and additional retirement savings. Even without working post-retirement, she was able to thrive off the retirement assets she’d accumulated. When you add her husband’s retirement assets to the mix, their lifestyle is equal to their pre-retirement income.

However, Davis-English is the exception, not the rule.

Dr. Angelino Viceisza, Professor of Economics at Spelman College in Atlanta, and research associate of the National Bureau of Economic Research, says that Black women have many structural barriers to achieving financial stability in retirement.

In his brief, “Black Women’s Retirement Preparedness and Wealth”, Viceisza studies single Black women and notes that they have an average retirement wealth of $11,157, the second-lowest average retirement wealth after Hispanic women. This means, as a group, they are not considered retirement-ready, and in fact, they often retire into poverty.

According to the Social Security Administration, in 2021, $13,363 ($1,113 per month) was the annual average Social Security income received by Black women 65 years and older. The maximum Social Security benefit available in 2023 is $4,555 per month, depending on lifetime earnings and age of retirement. The earliest age to begin collecting Social Security retirement benefits is 62. With Black women’s life expectancy at 75 years, there isn’t much time or resources to enjoy the golden years.

Viceisza finds that employment discrimination, low housing equity, health drains on savings and limited intergenerational wealth transfers are key factors contributing to low levels of retirement wealth for Black women. While they have a slight edge over other women in financial literacy, that isn’t enough to change their circumstances.

“There is a financial literacy component to why perhaps they’re not as prepared for retirement. The real big component is that they just don’t have enough wealth that they are inheriting, generating and are able to pass along to their children.”

He believes that Black women reinventing themselves after retirement is a way to circumvent the economic disparity.

At age 49, Darling “Diva” Moore of Denver, Colorado, did the math on her retirement.

“I started saying, ‘Wow, I am about to turn 50, and the only thing I have to look forward to is Social Security’. And when I looked at it, I saw shoe money.”

Moore’s plan is to retire at age 62, and she will receive $2,000 monthly from Social Security. If she had chosen to wait until age 67, her Social Security income would only increase by $100 per month.

When she looked at the numbers, that was not enough to afford the lifestyle she was currently living with her husband if he were to pass away first.

“When you tell a man, your man, your husband, ‘I’m worried about what would happen to me if something happened to you,’ the first thing out of their mouth is to remind you they have life insurance.”

Statistically, Black men live on average to age 69, leaving many wives to live out their retirement as widows. Moore and her husband crunched the numbers together to gain a mutual understanding.

“I literally had to sit down with my very educated husband, who’s an engineer and got math on lock, and show him that, ‘the money put away for me to live off if you’re gone, don’t even take care of our mortgage, Boo’.”

With this revelation and her husband’s support, she spent a year devising a plan to reinvent herself to supplement her income.

At age 50, she finished her bachelor’s degree and immediately started on her master’s. Her plan is to work in corporate until retirement and then use her newly acquired education to pivot into entrepreneurship as a private practice social worker.

In the meantime, she provides counsel to other women to get their Social Security Statements early to prepare for retirement. Her main focus is to help them figure out what they “want to be when they grow up” and devise a plan to make it a revenue stream.

Viceisza found that some who aren’t able to pivot into working after retirement often look to their children as a source of help to supplement their lifestyle.

Moore says that’s not an option.

“I have no intention of living with my daughter; I see the way she keeps her house.”

Dorothy Bridges of Minneapolis has over 45 years of working in the financial services industry, and she teaches her children and others about financial security. She has yet to retire, and although she feels prepared, that wasn’t the case early in her career.

“I learned a few things going through the school of hard knocks because I don’t think we even think about asset building when we are fresh out.”

Bridges says Black women should begin thinking about retirement as an investment in themselves. She advises starting as early as possible and looking into hiring a professional to help navigate the process and find the right mix of assets, such as real estate, stocks, savings accounts and 401(k)s.

“Make sure you understand that when you’re very early in your career, you may not be able to afford to put away the maximum into your 401(k) or other assets, but at least try to put away enough for the company to match your contribution.”

Bridges comes from a family of sharecroppers in Mississippi and knows the obstacles of learning about finance on your own, growing up without an inheritance, and the difficulty of saving when you may want to spend. She understands the need to sacrifice, change course and start fresh.

“I tell my kids, ‘short-term sacrifice for long-term gains’.”

Is Your Job Keeping You Single?

Over 66 percent of Black women are single, and almost 40 percent have never been married, as highlighted by the most recent census data.

While some Black women embrace the single life with no immediate plans to resume dating, others look at all their accomplishments at work, realizing that the heavy burden jobs place on Black women doesn’t leave much time or energy for romance. Many have to scale back on their work commitments to make time for romantic relationships.

Black women are opening up about the role their career-choices play in their love story.

Take Marin Heiskell, a senior manager at Deloitte in Chicago, for example. Marin is accomplished with three degrees from Ivy-League schools and a bright career ahead of her. She has a demanding job that she enjoys. Her consulting role requires 40-45 hours a week of client work plus an additional 15 hours per week participating in panel discussions and supporting research and recruitment. There is also a lot of travel with her role, and although travel has died down since COVID, and she can make more time for the people she loves, it wasn’t always the case.

“I’d be on the first flight out Monday morning, come back late Thursday night or even Friday morning, and then spend the weekend resting, recovering, doing laundry and repacking.”

Marin found that some men didn’t understand the nature of her job or why she was required to travel so often, which became a barrier to sustaining relationships.

“I think they are saying it from a place of both insecurity and just not being exposed to a lot of different types of careers. As a Black woman who works in consulting, I feel like people know the demands of a doctor, a lawyer, an engineer or a banker but question the demands of my job.”

Dating expert M3rry works with smart, successful, busy Black women, guiding them through dating. She says she often hears that men are intimidated by successful Black women.

“If you are a woman that likes to live well and likes the luxuries of life, and he can’t provide it for you, then he is intimidated by you because you can provide it for yourself.”

Marin’s had to vet prospective partners differently and change her mindset. “In the past, I’ve said to myself: ‘I’m not married, and I don’t have any kids, then there’s no excuse for me not to be at XYZ level. And so, I gun really hard, kind of forgetting I’m cutting off my nose to spite my face.”

Dating coach, Anwar sees this scenario play out often with his clients. He believes that many Black women are programmed by their parents to focus on security and to make sure they can take care of themselves, which translates to education, jobs and money. Romance often gets pushed to the side to ensure survival, which equates to putting most of their time and energy into having a successful career.

“No, your job isn’t in the way because you have a boyfriend already, your career. And you are giving this career emotional, mental and spiritual space.”

M3rry agrees. She acknowledges Black women have the pressure of success that may not be placed on other races of women. According to her, what’s really keeping them single is their lack of priorities, non-congruency and failure to include other races in their dating search.

“Does it matter if he’s Black? Does it matter that he looks a certain way? Or do you want to be taken care of? Sometimes what my clients say they want doesn’t match up to the men they are describing.”

Anwar believes that, even if the right guy presents himself, if Black women don’t have career boundaries or a level of vulnerability, starting and maintaining a successful romantic relationship will be challenging.

“If you are not vulnerable, it’s going to be really difficult for you to deeply connect with the man because it’s your vulnerability that is going to inspire his.”

He also says that many Black women have to learn how to date because it’s not something taught by most Black parents.

Fila Antwine, a relationship coach, also teaches her clients how to date. “Black women are not taught how to be partners, and we are not prepared for partnership.” She says that at a very young age, Black women are taught to protect themselves from men and to disconnect to achieve their goals.

“We are taught how to survive without men the first half of our lives.”

Fila says career success and accomplishments become a source of pride and self-worth, but that narrative has to change to have their desired partnerships. She says that Black women are taught to be self-reliant and independent when real partnership comes from collaboration and being open to connecting with others.

“Black women have to dismantle all of the things they’ve built for themselves and figure out who they are and what they want.” She says for many, there isn’t any time to waste.

“The time is now. There is no f*cking clock.”

The Co-Parenting Tightrope: Its Impact on Your Career

Navigating co-parenting as a single or newly separated/divorced parent may not initially seem like a workplace issue. Still, its ripple effects permeate every part of life—positive and negative—and can affect job performance. For some, a dysfunctional parental relationship can include constant arguing, refusing to communicate or unpredictable visitation, which can result in missed meetings, late arrivals, having to leave early, calling in at the last minute, court dates and being distracted with phone calls.

Alysha Price, founder of The Price Dynamic, a professional family coaching and engagement consulting firm, sees this behavior often with her clients, including single and co-parenting families, struggling to create a functional structure that allows each person to flourish. A product of a co-parenting single-parent household, Price found herself in a difficult co-parenting relationship and used what she learned to create a better environment for her son.

“In my process of parenting, I realized how much I was repeating things that I had grown up around, things that happened in my household. I realized how much I wanted to change some of those things and improve.”

When it comes to the effects of co-parenting on job performance, Price says many are unprepared for the toll it can take on their careers.

“You’re present, but you’re not mentally present. You’re spending a lot of work time contacting attorneys, navigating school and those types of transitions that happen.”

Price says that aligning what happens after school and who picks up or drops off the kids to their extracurricular activities can be stressful for parents trying to deal with their emotions from the relationship breakdown.

The stress can also fuel illnesses for the adults and their children, causing more missed days at work.

“You’re being somewhat of an executive assistant to your new family dynamic, and attendance is severely affected by illness. When your child is moving back and forth from one household to the next, things are affected, like their sleep and stability, which, of course, adds to their not being well.”

Marissa Johnson understands the effects of parental relationships on a family’s ecosystem. As a licensed clinical social worker, she works with adults and children to help them work through issues that impact every facet of their lives, including co-parenting, which can tremendously impact the workplace. When she found herself in a dysfunctional relationship while pregnant, she had to take stock and change course.

“I tried to keep the relationship going, and then when I was about seven months pregnant, I was just like, ‘nah, I’m not going to do this.’”

Johnson had a difficult co-parenting relationship when her daughter was born, which spurred her to start grad school so she could eventually find employment that paid enough to support a single-parent household. In the second year of grad school, she quit her job to focus on school alone and survived solely off student loans.

“When we were going through the courts, I was doing my internship in grad school. We had to do a practicum, and I remember I was so emotional because we had court the day before, and I had to explain to them why I couldn’t even get through a sentence.”

The stress took a toll on her mental health.

“It impacted how I was showing up in my classes and at work. I wasn’t able to give my full self.”

Johnson says her supervisor, a Black woman, also a single mom, helped her through the situation and didn’t make her feel embarrassed when she shared her situation.

Price explains that it is important for supervisors to be empathetic, but worrying about their employees with co-parenting issues can take a toll on the company. She developed “Family Meeting Cards” to help families make better decisions that can reduce the negative impact on their careers.

“We give our clients tools that put the onus back on the employee to deal with their family dynamics, but in the same sense, teach effective communication skills and skills to discern what is appropriate to share at work.”

TaShara Caldwell knows all too well how family dynamics can impact career paths. A paraprofessional completing her internship for her master’s, she has to give 600 hours of free labor on top of her current job, which has prolonged completing the requirements.

“It’s hard to do that when you’re trying to also work and work around someone’s schedule.”

She and her ex-husband, a firefighter with an unpredictable schedule, often barter and negotiate who will take off work when their child has a doctor’s appointment, is sick or has a school function. Caldwell says early in their separation, communication was rocky.

“We would get in these battles of who is going to take off work, kind of whose time is more valuable than the others.”

Caldwell looked to couples counseling, even though divorce was eminent, to figure out how to navigate their new dynamic.

“His schedule is going to be his schedule and I am going to be a mom forever, so even though we are not together, we share a Google Calendar.”

She says even with the shared calendar, when she has to take off work unplanned, it impacts her job even though it is common practice for moms to leave work to take care of their children.

“Schools automatically call mom, even though they have both numbers, they just call mom.”

Sometimes Caldwell’s supervisor will ask if her ex-husband can go instead, often followed by personal questions she does not want to answer.

“It’s frustrating because you don’t want to tell everybody your business.”

According to Price, when the co-parenting relationship begins affecting job performance, employees should keep their chats with managers “brief to minimum” while communicating their needs and leave out details that are not necessary to share. She recommends talking with human resources to ensure a documented paper trail.

When the parents cannot work together constructively, parallel parenting may be an option. This method allows each person to parent separately in all aspects of their child’s life, including doctor’s appointments, sports games and birthday parties. Text-only communication or using apps, such as Talking Parent, may stop parents from disruptive, negative communication yet allow them to keep abreast of schedules that include work trips, conferences or shift changes.

Johnson says text-only communication worked the best for her and her co-parent. Their relationship and her career improved when she took her emotions out of the situation and focused on herself.

“It’s very possible for you to have everything you want career-wise and still be a good mother. When things like this happen that set us back, like having to co-parent with people who aren’t easy to co-parent with, you start to develop these beliefs that it’s not possible or it’s too hard. You can’t do it.”

Shaping Corporate Leadership: Black Women on Boards

Investor, advisor and board member of The Harvard Business School Club of New York, Tamara Bowens, is an expert in sales, branding and partnership marketing. Her current board appointment was announced in August 2023, and while it’s not her first time serving on a board, she feels it expands her reach and allows her voice to be heard.

“That’s something I’ve always tried to do is be true to who I am, no matter what room I am in, and if I know that I’ve been true to myself, then I know that I have a real seat at the table and I can make a real impact.”

Sulamain Rahman, CEO at DiverseForce in Philadelphia and board member of Lendistry, is a board matchmaker. His program, DiverseForce On Boards, prepares high-potential middle to senior-level leaders of color to expand their capabilities through a board training and matching program. He says just having Black women on boards isn’t the solution, but making sure those appointed are there to move the needle.

“The reality is, it’s not really about just having Black and brown faces in high places, but how do we make sure our presence is felt in those spaces? Unfortunately, many people don’t sign up to be civil rights leaders, if you will, when they’re on boards.”

As a Black woman, Bowens is given the opportunity to share her vast business experience and unique perspectives on issues that may go unnoticed without representation.

“There have been times when there has been a discussion about things that are ‘culturally difficult’, is a way I would put it. But then I have to be the one in the room to raise my hand and go, ‘oh, but yeah, I understand your point of view, but let me just tell you how people who look like me feel’.”

Miquel Purvis McMoore, of Minneapolis, serves on various non-profits and a Life Advisory Board position for Wise Inc., a corporate board. She is also CEO of KP Companies, an executive search firm in Minneapolis that recruits to fill board seats. She sees more boards actively looking for Black women to serve as leaders and says Black women who want to be on boards should prepare themselves early.

“Depending on where you are in your career would determine how you should prepare yourself for board readiness. I think the skills you gain, obviously, on your job, your organizational skills, project management skills and specialty skills, such as accounting or legal.”

Rahman wants upcoming leaders to understand that their diversity is invaluable, but they also need expertise, confidence and broad experiences to be effective company leaders.

“The CEO is going to that board, reporting to that board, and is providing oversight as well as strategic advice on how to take that organization to the next level.”

Rahman encourages those interested in filling board seats to start with non-profit organizations to gain experience. Some of those positions are paid, but most board members start with volunteer boards.

According to McMoore, networking and letting folks know you are interested in bringing your skills to companies is another important way to be placed on the shortlist.

Black and White women in the workplace

The rise in racist activity showcased by white women in public spaces across the nation has caused an awakening in the role white women play in Black women’s oppression. In many of these incidents, white women—referred to as Karens—assault, hurl racist slurs, physically restrain, question, and taunt Black women while calling the police, further endangering the lives of the people they harass. When these white women are fired from their jobs for this behavior, others have come to their rescue, stating that losing their jobs should not be a consequence of their dangerous public outbursts. Many fail to realize that these dangerous behaviors hide in plain sight at work to the detriment of Black women’s careers and mental health. Moreover, they affect how Black women patients, customers, and business partners are treated.

“Our data tells us that Black women are having their worst experiences when they report to white women”

In light of these incidents, Black women are speaking more openly about how white women negatively impact their workplace experiences, derail their careers, and harass them in the office.

“I’ve dealt with many Karens in my career,” says Dr. Michelle Wilson, director of Evaluation and Learning at the National Fund for Workforce Solutions. Black women cite white women as a major cause of workplace discrimination and harassment, which leads to anxiety, depression, job loss, and a mass exodus from corporate America, non-profit organizations, and academia.

“Our data tells us that Black women are having their worst experiences when they report to white women,” says Cierra Gross, founder of Caged Bird HR. She says it is ironic that white women benefit most from affirmative action, “yet they are perpetuating the most harm in the workplace.” This harm affects Black women’s ability to advance in the workplace and earn the wages they deserve.

Companies that advance gender as their diversity focus often miss the unique intersectionality of race and gender that affect Black women. This places white women at the forefront to benefit from these programs while Black women remain invisible. When white women receive power in the workplace as a result of these programs, it does not often translate to better opportunities for Black women, including overall culture improvement, job titles, positions, responsibilities, and wages.

Françoise Burgess writes in The White Woman: The Black Woman’s Nemesis that “Black women have accused white women of being duplicitous; while they proclaim sisterhood in theory, they are unable to overcome their racial prejudices in practice.”

Overall, although women are advancing in the workplace, white women continue to move up the corporate ladder while Black women remain at the bottom while being gaslit to “Lean In”, be more social and take on difficult tasks for lower pay. Many corporations believe that by advancing white women, Black women will also benefit, but that is not the case.

Author Vivian Gordon says, “Seldom attention is given to the extent to which white women benefit from the oppression of Black women.” She explains, “white women are saying to the white male power structure: Move over. We want to be part of the power structure. Black women are saying: ‘The structure is wrong.’”

In the LeanIn.org and McKinsey & Company’s 2022 Women in the Workplace Report, only 44 percent of Black women reported feeling comfortable disagreeing with coworkers, whereas 57 percent of white women felt free to challenge or have differing views. This can translate into Black women not voicing their professional opinions or concerns about mistreatment for fear of retribution or white women’s tears.

“There is nothing more dangerous to a white woman than a competent Black woman”

A TikTok trend in 2022 showed white women’s collective ability to cry on command. This terrified many Black women who have been the victim of this weaponization. Black women are labeled aggressive, unprofessional and mean when white women cry unprovoked during professional communication exchanges. Luvvie Ajayi calls it the “weary weaponizing of white women’s tears.” Where they claim to feel personally “attacked” and “targeted” when questioned, given feedback or held accountable for their actions. Crying or playing the victim as a tactic allows others to focus on the white woman’s perceived trauma with sympathy instead of the actual trauma she may have inflicted on the Black woman, rendering them invisible yet again.

Writer Zora Neal-Hurston believed the modern relationship between Black and white women is patterned after the relationships on the plantation, where the white women used their power and white fragility to their advantage. “Thus, from the beginning, the seeds of resentment between Black and white women were sown…”

Slavery was the birth of this complicated relationship. Just as Black women can pass on trauma from that era, it is no surprise that white women may continue generational behavior patterns, whether intentional or unconscious.

Despite the early relationship formed during slavery, Black women do not feel unequal to or jealous of white women. “[Black women don’t have] envy for their accomplishments,” writes Toni Morrison. She goes on to argue that Black women also have no sympathy for white women’s perceived oppression.

On the contrary, Black women feel some white women are jealous and afraid of their power and abilities in the workplace. “There is nothing more dangerous to a white woman than a competent Black woman,” says Dr. Angela Neal-Barnett, director of the Program for Research on Anxiety Disorders in African Americans (PRADAA) at Kent State University in Ohio.

Gross says it is difficult to change this problem when Human Resources is a white woman-dominated field. In 2020, Data USA reported 76.8 percent of human resources managers were white, with 64.1 percent white women. Human resources is the department whose purpose is to create and enforce workplace policies. Bias and racism are dangerous in this area of the company. If Black women see white women as a threat to their careers, it could be a significant factor in why the issues seem exacerbated in the workplace with Black women feeling unheard and unsupported.

“Seldom attention is given to the extent to which white women benefit from the oppression of Black women”

In the book, Ambition in Black + White, Melinda Marshall and Tai Wingfield agree that Black women and their unique struggles are invisible in the workplace. Yet, their research found that, unlike their white counterparts, Black women are 25 percent more likely to have both near-term (50 percent vs. 40 percent) and long-term (40 percent vs. 32 percent) career goals and are more confident that they are qualified to succeed (43 percent vs. 30 percent) in a position of power.

Marshall and Wingfield also write that Black women are three times as likely as white women to aspire to a powerful position with a prestigious title, as they are often inspired by the matriarchs of their families who prevailed as breadwinners and showed their power and ingenuity without access to the higher levels of opportunities. This data does not correlate with the positions Black women hold or the perceptions that they lack initiative.

How do we fix this?

Racism in the workplace is not Black women’s issue. It is a white issue and something that has to be addressed if businesses want to continue to benefit from Black women’s undoubted contributions. At the same time, the responsibility for building a professional relationship between white women and Black women lies with white women who hold more power in the workplace; and who continue to choose whiteness over gender solidarity, as illustrated in the last two presidential elections.

There are Black women who are doing the work to bring these issues to light, from authors and activists to academics. Neal-Barnett teaches a course called The Psychology of Black Women, which has a waiting list. She says when white students come out of the course, they are blown away at how Black women experience and navigate the world. “Many of them are like, ‘We didn’t know.’ She says they never talk about Black women, so they are ill-equipped when they get into the workplace. “They have limited to no insight into what it means to be Black and a female. They don’t know, but they should hear enough cases after a while.”

Director of Evaluation and Learning National Fund for Workforce Solutions

director of the Program for Research on Anxiety Disorders in African Americans (PRADAA)

Kent State University in Ohio

founder of Caged Bird HR

Contact us

Betting on yourself: leaving corporate and starting your business

Layla Nielsen knew when it was time to “jump out there and launch.”

She had already built a significant digital media portfolio freelancing for 10 years while she worked as an executive for large media companies. So, when she parted from her last agency job, she thought it was time to start her own.

“I wanted to create the kind of environment where I could be more successful,” says Nielsen, owner of LN & Co, a digital agency in Silver Spring, MD.

Neilsen couldn’t bring herself to work for one more company that glossed over her accomplishments and required her to work at a level lower than her resume should’ve commanded.

“I was coming from an environment where I led everything.”

Her experience is all too familiar. Black women are leaving behind the notion that corporate America or being an employee is the only option for career fulfillment, especially after years of being glossed over for promotions, accepting less pay, and working in cultures that felt exclusionary. Many find that going out on their own allows them to play to their strengths, deliver higher-level work product and create a culture that works best for them.

According to a 2021 Harvard Business Review report, entrepreneurship offers opportunities for Black women to elevate their careers and achieve social and economic equality.

“If there is something on your heart that just will not die, don’t keep pushing it aside. Learn everything you possibly can about it, and then get started.”

Nichole Jean Philippe started The Gallery Grid after moving her family back to Maryland from New York to help her parents after her father suffered a stroke. Her company, which provides art consultation services and installations for businesses and private homes, was developed out of need and ingenuity.

“I’ve always loved working with my hands. My father was very handy, and my mother is incredibly innovative.”

Jean Philippe says that when she bought her first condo in New York, she had a difficult time creating the perfect gallery wall without making numerous holes in her new walls. After spending three days trying to hang a four-piece mirror perfectly, she felt there had to be an easier way. She took her previous experience as an executive product developer in the fashion industry and used it to communicate, negotiate, source and eventually develop a product. Her first stab at the creative process didn’t go as planned, and she went back to work but didn’t give up.

She continued to develop The Gallery Grid in her spare time, helping friends and family select and install art for their homes. After sharing a huge cost-saving idea with her employer that Jean Philippe found through her sourcing expertise, she was pushed out. Her employer told her without warning or reason that she had to choose between the job and her hobby.

“They hired me knowing about my idea. We talked about it during the interview process, and it was on my LinkedIn page. Then all of a sudden, after four years, they decided it was a conflict of interest and gave me an ultimatum without any discussion.”

Jean Philippe says she was blindsided and hurt by how she was treated. After that experience and reflecting on other disappointments throughout her career, she decided it was time to turn her hobby into a business.

“It’s just sad to think about. I had taken a huge pay cut and was working below my experience level, but I needed to support my family. Now, I am so grateful and blessed, and I’m very confident that God has more for me in the future.”

Harvard Business Review found that 17 percent of Black women are in the process of starting or running new businesses, compared to 10 percent of white women and 15 percent of white men in the United States. Moreover, Black women entrepreneurs are highly educated, with more than three-fourths with at least a college degree.

While starting a business can be a gateway to financial freedom, it’s not easy. Black women face more financial barriers to growing and sustaining their businesses, including funding and support from both the public and private sectors. The report states that 61 percent of Black women self-fund their total start-up capital.

Neilsen and Jean Philippe both run self-funded businesses, which is the reality for most Black women. They both recommend building a financial cushion before you start your own company. “An entrepreneurial journey is rocky—one month you might be making six figures, and the next month you might be making zero,” says Nielsen.

She doesn’t want that to discourage other Black women from building a business and wants them to believe in every possibility. “You’re smart. You’re good enough. You have the track record. You have the degrees; you have the experience. You’ve got it all.”

Jean Philippe advises, “If there is something on your heart that just will not die, don’t keep pushing it aside. Learn everything you possibly can about it, and then get started.”

founder and CEO

LN & Co.

owner and principal designer

The Gallery Grid

Hair as healing: the healing power of Black hair salons

“There is power in community, and I saw that growing up the daughter of a salon owner… I watched my mother nurture and heal those women in her salon, not just by making them look and feel beautiful but by talking with them, listening to them, and connecting with them. I’ve seen how much Black women’s emotions are attached to our hair and beauty.“

– Beyonce – Harper’s Bazaar interview August 10, 2021

Black hair is art, a language linked to our history and a part of our identity. Our hair affects how we see ourselves and how we are perceived in the world. Bursting with expression, it is deeply tied to those who have our permission to touch our hair. That’s why the relationship between Black women and their stylists is sacred, and the time spent in the shop should be therapeutic. Dr. Afiya Mbilishaka—head of psychology at the University of the District of Columbia, hairstylist and founder of PsychoHairapy—believes the link between routine hairstylist appointments and therapy can be a gateway to improved mental health. “Rituals are how we prepare our mind, body and spirit to receive something or do something,” she says. “The ritual of haircare…can help ready yourself for what you are about to face.”

Work is key to economic survival for most Black women who have a more difficult time than their peers coping with the unique stress associated with their jobs. “Half of my clients hate their jobs,” says Kay Simpson, owner and stylist at True Perfection Salon in Houston. “As I listen, I hear that many of them are there for the pay and not because they love it or feel supported,” she says.

“hair dying and cutting are ways Black women can express grief and loss.”

When clients are in the chair, they often share personal information with their stylists, who become pseudo-therapists, listening and giving advice after they have established trust. “Hairstylists are sort of a keeper of secrets,” says Mbilishaka. She trains hair care professionals in the art of active listening through her PsychoHairapy practice. She works with them to relax the natural instinct to give clients advice. “I recognized the hardest skill I had to learn as a therapist was how to listen. It’s really difficult.” She cautions that while in the chair, only part of the story may surface, so it’s best to be a safe place for the client to vent instead of looking for solutions.

In addition to listening to clients’ stories, hairstylists can hear what isn’t being said by evaluating the hair. “I’ve had clients whose hair is shedding, and the density has changed because of emotional stress from work and life,” says Simpson. Drastic changes to hairstyles can also be a sign that something is going on with the client. Mbilishaka says that hair dying and cutting are ways Black women can express grief and loss. Hair can also communicate if the client drinks enough water, sleeps and eats the right foods.

Stylists aren’t certified therapists, and that can be a heavy burden to place on them. For this reason, Mbilishaka focuses on practical skills in the PsychoHairapy curriculum, such as how to assess whether a client should seek professional help, including signs that they may either be of harm to themselves or others. Stylists also learn the distinctions between various mental health professionals and how clients can benefit from being connected to the right source. “Everyone gets a certified list of curated providers in their area so that if they want to refer a client to a therapist, they actually have names, locations and websites to share,” says Mbilishaka.

“Hairstylists are sort of a keeper of secrets”

Simpson agrees that it is vital for hairstylists to be able to see the signs that their clients need to seek professional help. However, she adds that mental health professionals should better understand the positive effects hair can have on their clients. “I wish doctors would prescribe for women to get their hair done as a part of therapy because it lifts their mood and can change their perspective.” According to Simpson, a new do can improve clients’ spirits. “I’ve seen women come in here feeling ‘a way’ and leave ready to go to happy hour or go back to work ready to slay.”

While many stylists focus on providing a service and helping their clients, Mbilishaka says they also need to practice self-care. “Hair care professionals actually need more detoxing, more self-care, more massages, more eating healthy, more comfortable shoes, more community and more water than other people.” She hopes to offer stylists retreats where they can receive the reciprocal opportunity to be loved, cared for and comforted to feel safe.

Busting workplace myths for success

We caught up with Jessica Ekong, chief human resources officer at Providence St. Joseph’s Health in Los Angeles, who graciously took us on a journey debunking seven pervasive myths that often hold Black women back from career success.

Myth one: If you keep working hard, good things will happen to you

We have all heard the saying, “work smart, not hard,” which applies to those picking up extra tasks around the office or focusing on internal organizations instead of showing excellence in their roles and responsibilities. If you are killing it in your role, taking on leadership roles in other areas can be beneficial, but ensure you focus on your primary responsibilities at the company. When you are exceeding expectations, ask yourself if the right people in your organization know the amazing work you are producing and whether you have advocates speaking on your behalf. This will make the difference in being recognized for your accomplishments and contributions that hard work cannot do on its own.

Myth two: The best time to ask for a pay increase is at your performance review

Understanding how your organization works, including knowing the pay review schedule, is essential to timing the ask for a higher salary. While they are typically 90 days prior to your part in the review process in larger organizations, you can request this information from human resources or your manager as early as the initial interview and at any time during your employment. Having this information can save you disappointment from asking for a raise when there either isn’t money available.

Myth three: When you are in trouble, keep it to yourself.

When people are in trouble, they wait too long to tell someone. The first step is to immediately talk to someone you trust within your organization who will give you honest and clear feedback. Figure out how you want to handle the situation before you seek advice. When you tell them the scenario, follow it up with a question, “Here’s how I’m thinking of proceeding. Do you have any guidance?” Always ensure you have a paper trail that helps keep you accountable and protects you. If your mental health is being affected, you can seek out the Employee Assistance Program (EAP) in your organization to get a referral for a licensed therapist.

Myth four: Every opportunity is an opportunity to fight

There may be instances to file a complaint with human resources or even the EEOC. Still, sometimes for mental health and sanity, it’s better to bow out gracefully and negotiate an exit package that gives you time and resources to find a better opportunity.

Myth five: You have friends at work

As human resources professionals, we constantly hear, “HR is not your friend,” when the truth is no one is your friend, this is a business. It is important to figure out who your professional allies are and who supports your career, but don’t mistake professional courtesy for friendship.

Myth six: Being happy to be there is a flex

There’s something about fancy brands that get folks caught up. Taking a lesser role or staying too long at a well-known company with big-name recognition is a common career mistake. Staying at a company simply because you like being associated with the name or status, and not because it serves you and your goals, is not a mature career choice. When you are simply happy to be there, companies know this and handle you accordingly. They know they don’t have to hire you at top dollar, promote you or increase your pay, so they don’t. In other words, “don’t let your employer be your God.”

Myth seven: Being unsuccessful at one company means you’ll have the same experience everywhere.

Just because you’re not shining in one place doesn’t mean you are not a star. Sometimes one company is not a good fit, or they don’t see your value. Don’t let that hold you back. You may join another organization that celebrates your contributions and pays you what you’re worth.

chief human resources officer

Providence St. Joseph’s Health in Los Angeles

Is it you or discrimination?

How documentation helps determine behavior change or complaint filing

Documentation is an important tool for effective communication, accountability and self-awareness in the workplace. It can also be a protective measure in distinguishing between self-inflicted maltreatment and discrimination.

“When it comes to protecting yourself, it’s really important to be honest about yourself, to be honest about the situation, to be honest about where you are because sometimes it’s you,” says Adebisi Wilson, an attorney in Minneapolis.

Wilson cautions that before employees go down the road of talking to human resources (HR) about discrimination, they should look honestly at their communication style and performance. “You may find that you didn’t do that thing on time, then you got three extensions,” she says. “Then when you submitted it, you felt like you did something really big, but it wasn’t what it could have been had you done it right the first time.”

She says there is nothing wrong with admitting your methods or behavior needs to change and seeking help from a trusted resource within the organization to give honest feedback. “One of the things that I find is that a lot of us are navigating this business world for the first time, and some of the things that we’re encountering, we don’t know how to handle, or we take it personal when it’s really business.”

After self-reflection, many Black women who find that they are, in fact, being treated unfairly because of their race and gender look for ways to protect their career and reputation. Wilson says that falsely accusing employees of performance and behavior issues are ways employers cover up their discriminatory practices. “A lot of clients feel like they’re being gaslit; they feel like they’re just crazy,” she says. “The only way to figure out what is really happening is to document everything.”

Forms of documentation may include keeping all emails to and from your manager, sending meeting recaps, immediately writing down occurrences in a notebook while they are fresh in your mind, and recording conversations if that is legal in your state.

“Employees are thinking everything is all good, or they are kiki’ing and the employer is thinking you should take some form of learning from the kiki.”

When it comes to adverse actions, such as being placed on a performance improvement plan (PIP), Wilson says the majority of her clients are blindsided by this form of discipline. She says it is vital to ensure documentation is timestamped and clear at this point in the process. In addition, she says that her clients find coaching sessions that lead up to the PIP or are a part of the PIP can be conducted in a confusing manner and present as regular meetings or conversations. “Employees are thinking everything is all good, or they are kiki’ing and the employer is thinking you should take some form of learning from the kiki.”

Wilson says sending meeting recaps asking for feedback can help to ensure that all parties are on the same page and to have a record of the discussion. When you feel the treatment is unresolvable with management, seeking HR is the next step. “You go to HR, and they either handle it or they don’t, and if it continues, you can contact an attorney and make a complaint with the EEOC even before you’ve had an adverse employment action, such as a PIP or termination.”

When you contact an attorney after you believe you’ve been the victim of discrimination because of race, color, religion, sex, gender identity, sexual orientation, age, disability or genetics, they will want to see the documentation to ensure the case can be proven in court. “Without the documentation, it is their word against yours, making the case more difficult to win.”

attorney